Over $2 million and going strong ….

JJ Watt is raising money for Harvey’s disaster relief

To make a donation, either contribute to CleanWaterWarrior for a direct pass-through to Watt’s foundation, or click here: YouCaring.

Clean Land. Clean Water.

Over $2 million and going strong ….

JJ Watt is raising money for Harvey’s disaster relief

To make a donation, either contribute to CleanWaterWarrior for a direct pass-through to Watt’s foundation, or click here: YouCaring.

The tragic events affecting millions of people living in the path of Hurricane Harvey are being immediately reported and followed by scores of people around the planet. Harvey has been called a 500-year storm, carrying such force that there is in any given year less than a .002% chance of a storm of this power occurring.

The devastation is epic, and watching in real-time it is hard to imagine things getting worse. Although no estimates can be firm at this point, it is safe to say that bricks and mortar clean-up and reconstruction will take months, if not years, to complete.

Some of Harvey’s damage, however, is now more or less going sight unseen. It will, however, soon become all too obvious.

In the coming weeks and months, any who take a cruise through, or fly over, the Gulf of Mexico may see first-hand another awful bi-product from Harvey’s torrential downpours.

Perhaps even larger.

A discussion on whether this human-promoted environmental disaster could have at least been reduced in its magnitude is, at this point, idle chatter. This mess, unlike bricks and mortar destruction, cannot be repaired. It will not be halted.

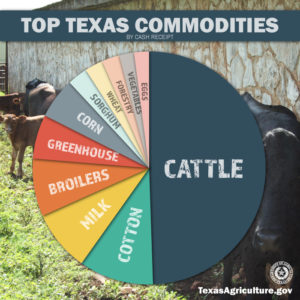

All this is 100% understandable – if not 100% preventable. It is about farm animals, and agriculture.

Lots of animals.

Lots of manure.

Lots of phosphorus.

Lots of Harmful Algae Blooms (HAB) creating lots of deadzones.

Hurricane Harvey has left a path of destruction that will take Texans years to repair. Sadly, for life in the Gulf of Mexico and for the many thousands people who make their living fishing the Gulf, or work in tourist trades that abound around the Gulf, the farm runoff damage this go-around cannot be undone. It will be massive, and irrevocable.

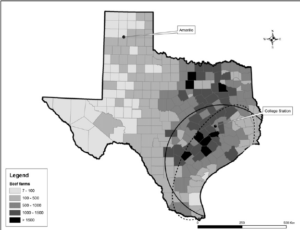

To the degree that farms provided insufficient grass buffers between waterways and cropped land, tilled marginally productive sloped acres, or — worst of all — poorly managed manure and fertilization levels, the environmental damage from Harvey will be proportionate to the negligence.

Fact: farms can always, within reason, do better managing land and manure.

The filthy aftermath of Hurricane Harvey will make that, in an obvious play on words, perfectly clear.

None of us would argue that efficiencies in agriculture — reducing costs to raise and harvest crops, and feed animals, for starters — have had a monumental and often very positive impact for consumers. Long story short: people need to be fed and, with a global strain of 6.5 billion, agriculture has come up with solid solutions for feeding the masses.

But producing efficiently is but one piece of the global agricultural puzzle. Another just as important component is conserving efficiently.

According to recent information from the USA chapter of the Union Of Concerned Scientists, the nationwide cost of farm runoff is hefty:

Water pollution from fertilizer runoff contaminates downstream drinking water supplies, requiring costly cleanup measures with an annual price tag of nearly $2 billion.

I would argue that this estimate is too low. A recent article in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune notes that the State of Ohio alone has received millions in aid to treat harmful algae bloom (HAB) activity and other agriculture pollution issues largely affecting Lake Erie.

The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative has spent millions on cleaning up beaches and restoring wetlands that filter pollutants along the lake shore. In all, Ohio has received just over $200 million in federal funding from the program since 2011.

While funding and incentives to improve land management from Federal and State government sources exist — through a variety of sources, like the US Department of Agriculture — to participate requires considerable effort, including an involved application process, on the part of farmers. If the financial incentive to implement better practices does not meet or exceed a crop-and-harvest approach, it is likely that only the most motivated (see environmentally friendly) farmers will apply.

What is needed is a strategy that rewards the farmers most economically challenged, or least concerned, to make permanent improvements to their land management practices. Depending on their location, these are the farms contributing most densely to HABs — farms which, within reason, are not necessarily of a particular size — that must be targeted for any real conservation impact to be realized.

Tracking the recent farm runoff legislation strategies in Iowa and Minnesota, it becomes clear – to the surprise of few – that attempts to formalize legislation aimed at curbing farm runoff will be met with staunch resistance.

This does not bode well for residences amongst and downstream of agricultural operations. Such operations continue to struggle with controlling the runoff they create from excessive animal manure.

A recent article by NPR (citing expert Greg Cox) discusses best

practices for reducing farm runoff. Ag runoff, as has been mentioned many times here, is the primary contributor to harmful algae blooms (HABs). As ever, best practices always include creating sizable grass buffer spaces between cropped land and waterways.

Grass which carries a clear benefit for farmers. It can (and should) be harvested to feed and bed farm animals.

Such a basic strategy makes great sense when proposed in a vacuum. But, for farmers striving to pull every bit of revenue from each acre, such an approach may not always make financial sense. And, clearly, farmers have little interest in more governmental involvement — as is presented regarding Iowa legal battles in this recent article from US News and World Report.

The push-and-pull here is inevitable, oh-so predictable, and the least productive method for solving the nationwide and global challenge of HABs.